Kashmir - Behind the camera

Filming in Kashmir meant keeping rushes safe, dodging stones – and persuading the locals that daily life was worth showing, says Catie White.

There was no amount of explaining to our local AP – who had a day job for a busy lawyer’s practice and was doing us a favour by stepping into the breach in a hostile region where having someone who can spot the difference between a street vendor and a government spy meant keeping hold of our rushes – what we meant by future tense. Or character development.

“Let us know when [Ms X’s] story moves on,” we tried, as he kept an eye out for the competing intelligence agencies that follow foreigners filming in the Kashmir Valley. “Tell us when something happens to [Y]. Alert us when a significant event in [the carpenter’s] life is about to unfold.”

A funeral. A memorial. A homecoming. These were simple things that could help us achieve an intimate and fluid life – and death – story in this Indian state divided between Pakistan and China. It’s one of the longest-running emergencies in the world, for so long off our screens, especially when the Arab Spring drew away the last Western reporters, despite hundreds of thousands of local youths coming out onto the streets, throwing stones at the heavily armed Indian security forces. The troops returned fire with live rounds.

We arrived in Srinagar, the summer capital of Kashmir, in spring 2011, determined to seek out articulate teenage demonstrators to follow, through whom we would learn about these mega—protests that terrified the Indian government. However, the Indian security forces were also filming the stone-throwing boys; police snatch squads were seizing them in nightly round-ups that made them fear all cameras. On the other side, the police and paramilitaries, who had already killed 118 protestors, some of them children, had taken to beating journalists to stop them recording the unrest.

As we wrestled with the unwilling on both sides of the barricades, another potentially unfilmable development crashed over us: a state-wide government crackdown, with roadblocks and curfews that put several of the towns in which we had started making headway off-limits.

Mass arrests followed, with tens of thousands seized. Which brings us back to character development: how could we shoot what could not be easily seen among people who could not afford to speak out, using the local team of irregulars who struggled with our methods?

This has nothing to do with brains. Our local ad hoc AP could speak four languages. However, in a conflict zone where a pro-independence insurgency has cost upwards of 70,000 lives and at least 8,000 civilians have vanished while in custody – far more than in Pinochet’s Chile – all of the events we exhorted our fixer to help us chart seemed to him too mundane for TV.

A family silently assaying their dead son’s school certificates. The tearful joy when a sister hugged a wounded brother unexpectedly released from jail. We captured moments such as these despite the crackdown, and uncovered a shocking story about how India had restored peace in the Valley. But all of it came to us through people forgetting we were there.

It took time. We filmed on and off over a year. We spent days drinking saffron tea, munching almond biscuits and waiting for lives to coagulate. And in a punch-drunk state like Kashmir, when you are in the right place and the talking begins, it’s unstoppable.

A youthful insurgent went into a trance describing the inside of an Indian torture chamber, where Urdu graffiti welcomed him to hell. A veiled schoolgirl revealed, for the first time, how she had been plucked from class in her uniform, tortured and raped. A father sat before passport photos of his two dead sons, telling how he would never stop fighting to convict the security forces who shot one and then, when he protested, drowned the second in the Jhelum River.

It was when we strove to cover a story that things stalled, like the time we drove for 18 hours to reach a border village where residents were said to be captives of the security forces. A checkpoint stopped us and a young captain turned us around, mumbling into our AP’s ear in Urdu: “If the foreigners talk to anyone here, you will get it.” This the AP fully understood, and dismissed. A lifetime of threats had made him immune.

My Tricks of the Trade

Spend time constructing a non-partisan local team to fix, translate and guide.

If appropriate, seek out the authorities monitoring you before they act. It defuses tension.

Assume that every time you are on the road, someone is rifling through whatever you have left behind in your hotel room.

Take digital security seriously, protecting and disguising your rushes, encrypting your emails,

and talking on the phone in the expectation that everything you say is being overheard.

Pack a cafetière and good coffee.

SECRET FILMING

Funding a film like this is always a challenge. Channel 4 came on board early and we hoped that would enable us to attract the co-pro money we would need to make this film possible.

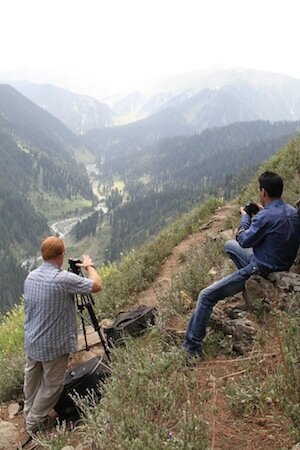

Sadly, we were unable to persuade our previous co-funders in the US or Germany that Kashmir was important enough to warrant this kind of investment. But we felt passionately that the tale of how torture is being used in Kashmir had to be told, so with the help of a modest, but much appreciated, advance against international sales from DRG, True Vision invested the rest of the shortfall and Jezza Neumann (pictured) and the team set off.

The film had to be HD-compliant, but also needed to be filmed as discreetly as possible. C4 made a special exception for Jezza to shoot HDV rather than full HD so that we could opt for a combination of Sony HVR-Z5 outputting the footage to a tape and card, and an HVR-A1 when even more discretion was needed. The HVR-A1 is ideal as once you’ve taken off the XLR and dispersed your equipment in bags or about your person, it doesn’t look at all suspicious. The only downside is that it records to tape, so you have to make sure you offload your footage as soon as possible.

The HVR-Z5, on the other hand, is perfect because, unlike tapeless cameras, you can put tourist footage on the tape and your real stuff on the cards; if you’re searched, you can hand over the tape and keep the card. Then back in the rooms, everything gets transferred to drives and put on hidden partitions, so it will take a seriously techy geek to find it. All our drives were then duplicated, with one set stored in a safe house.

One essential was protection when filming stone-pelting scenes. The team wore bump caps often used on building sites and Jezza had a motorcycle back protector.

Comments (Archive)

Posted by on 11-07-12

congratulations to the Director and team well done on showing this program.I will do something about this human sufferings and thats my promise to you my conscience doesnt allow me to do nothing and become couch patotoe! i wish to be part of the soloution than be part of the problem!